Maurizio Cattelan

Cattelan's personal art practice has gained him a reputation as an art scene's joker. All his works have a humorous twist. He has been described by Jonathan P. Binstock, curator of contemporary art at the Corcoran Gallery of Art "as one of the great post-Duchampian artists and a smartass, too". Discussing the topic of originality with ethnographer, Sarah Thornton, Cattelan explained, "Originality doesn't exist by itself. It is an evolution of what is produced. ... Originality is about your capacity to add."

Cattelan is commonly noted for his use of taxidermy during the mid-1990s. Novecento (1997) consists of the taxidermied body of a former racehorse named Tiramisu, which hangs by a harness in an elongated, drooping posture. Another work utilizing taxidermy is Bidibidobidiboo (1996), a miniature depiction of a squirrel slumped over its kitchen table, a handgun at its feet.

In 1999 he started making life-size wax effigies of various subjects, including himself. One of his best known sculptures, La Nona Ora (1999) consists of an effigy of Pope John Paul II in full ceremonial costume being crushed by a meteor.

Between 2005 and 2010 his work has largely centered on publishing and curating. Earlier projects in these fields have included the founding of "The Wrong Gallery", a store window in New York City, in 2002 and its subsequent display within the collection of the Tate Modern from 2005 to 2007; collaborations on the publications Permanent Food, 1996–2007 – with Dominique Gonzalez Foerster and Paola Manfrin – and the slightly satirical arts journal Charley, 2002–present (the former an occasional journal comprising a pastiche of pages torn from other magazines, the latter a series on contemporary artists); and the curating of the Caribbean Biennial in 1999. Along with long-term collaborators Ali Subotnick and Massimiliano Gioni, Cattelan also curated the 2006 Berlin Biennale. He frequently submitted articles to international publications such as Flash Art.[citation needed]

Cattelan's art makes fun of various systems of order and he often utilizes themes and motifs from art of the past and other cultural sectors in order to get his point across. His work was often based on simple puns or subverts clichéd situations by, for example, substituting animals for people in sculptural tableaux. "Frequently morbidly fascinating, Cattelan's humour sets his work above the visual pleasure one-liners," wrote Carol Vogel of the New York Times.

Cattelan utilizes media to expose reality as well as blur the lines between reality and myth. Several of Cattelan's works play off of the modern day spectacle culture. If a Tree Falls in the Forest and There is No One Around It, Does It Make a Sound (1998) is a piece that exemplifies this idea. The work consists of a taxidermied donkey with its head bowed low, carrying a television on its back. It is meant to conjure up the image of Christ riding into Jerusalem on a donkey, for Palm Sunday. The television taking Christ's seat on the Donkey serves a blatant representation of media culture's replacing tradition as the new object of praise. Hollywood (2001) is also re-figures a current reality in front of a new context. The whole of the work entails a giant replica of the southern California Hollywood sign overlooking a dump in Palermo, Sicily.

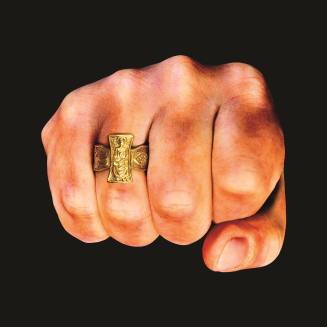

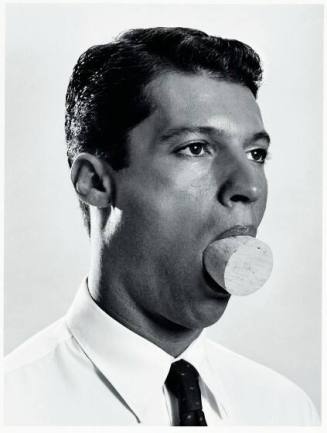

Cattelan's manipulation of photos and his publications of magazine compilations such as Permanent Food and Charley did not come about without their influences. The artist attributes his love of finding the uncanny, the silly, or the seductive in just about any mundane or sensational object, as traceable to the works of Andy Warhol. As Cattelan states, "That's probably the greatest thing about Warhol: the way he penetrated and summarized our world, to the point that distinguishing between him and our everyday life is basically impossible, and in any case useless."[10] Permanent Food and Charley differ in sophistication. Both consist of crude layouts, having magazine pages compiled together torn from outside sources. The latter, however, was backed by a wide list of recognizable and credible curators. His most recent publication, Toilet Paper, differs greatly from the two previously mentioned, as its photographs were originally planned and designated solely for the magazine.[11] The level of originality for this magazine surpassed the others, providing the audience vague, oddly familiar photographs to peruse through. Toilet Paper is a surrealist pantomime of images that the viewer cannot easily trace back to a starting point, while they've most likely been conjured by popular culture. It is a whirlwind of loud colors mixed in with the occasional black-and-white photo: "the pictures probe the unconscious, tapping into sublimated perversions and spasms of violence."