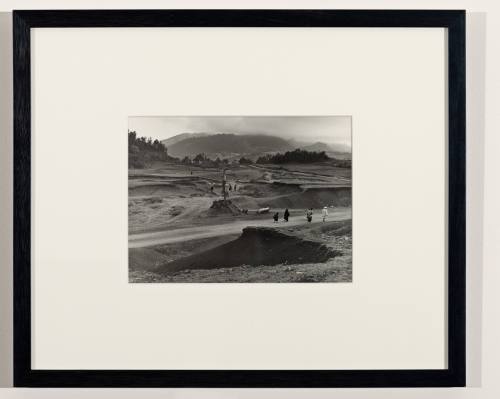

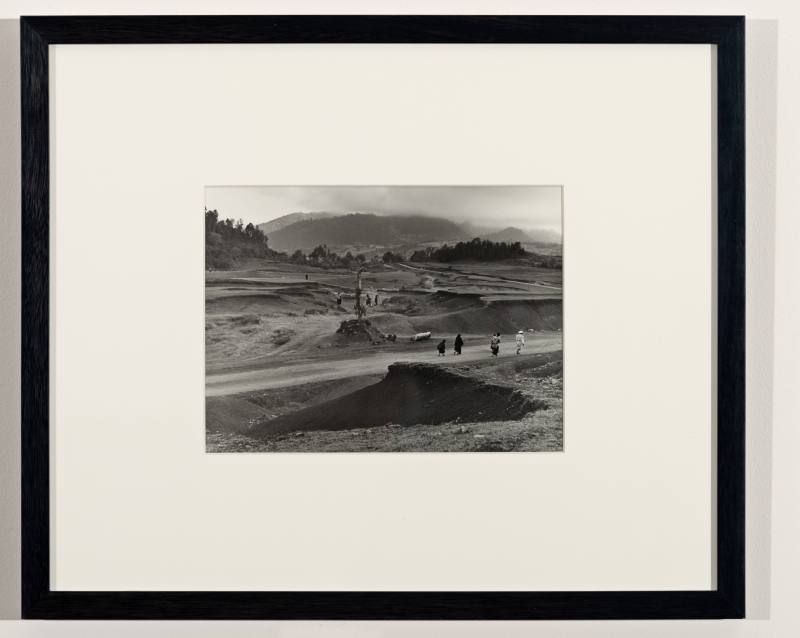

Manuel Álvarez Bravo

Mexico City, Mexico, 1902 - 2002

Person TypeIndividual

Terms

- Male

Hartford, Connecticut, 1928 - 2007, New York, New York

Bleckede, Germany, 1945 - 2007, Düsseldorf, Germany

Greenville, NC, 1925 - 2007, Berlin, Germany

Chicago, Illinois, 1939 - 2004, Chicago, Illinois

Greensboro, Alabama, 1939 - 1989, New York, New York